Aurora Australis 3

Credit here must go to Photo Pils for the bones of this post.

7 Key Factors Determining if You Can See the Southern Lights

Actually, the Southern lights actually occur all year long, and all day long. Yet we can only get to experience them when certain conditions all come together. These things are:

- The time of the day. It must be dark!

- Your location. Both in terms of actual latitude, as well as a location free from light pollution.

- The time of the year.

- The moon phase.

- Terrestrial (earth / land) weather.

- The solar weather / activity.

- Solar Cycle

1) Time of Day

Let’s break these down. You can see auroras at any time of the day as long as it is dark, there are clear skies, and solar activity.

However,

- The strongest lights tend to appear between 21:00 and 2:00, though the best sightings often occur between 23:00 and midnight. That’s because, even after the sun goes down, there’s still a little bit of light left in the sky for a while.

- Between 04:00 and 17:00 there is generally too much daylight to see the aurora.

- Exceptions are the darkest months of the year and higher latitudes, where it is dark 24/7. In the Southern hemisphere this tends to be from mid-May to the end of July.

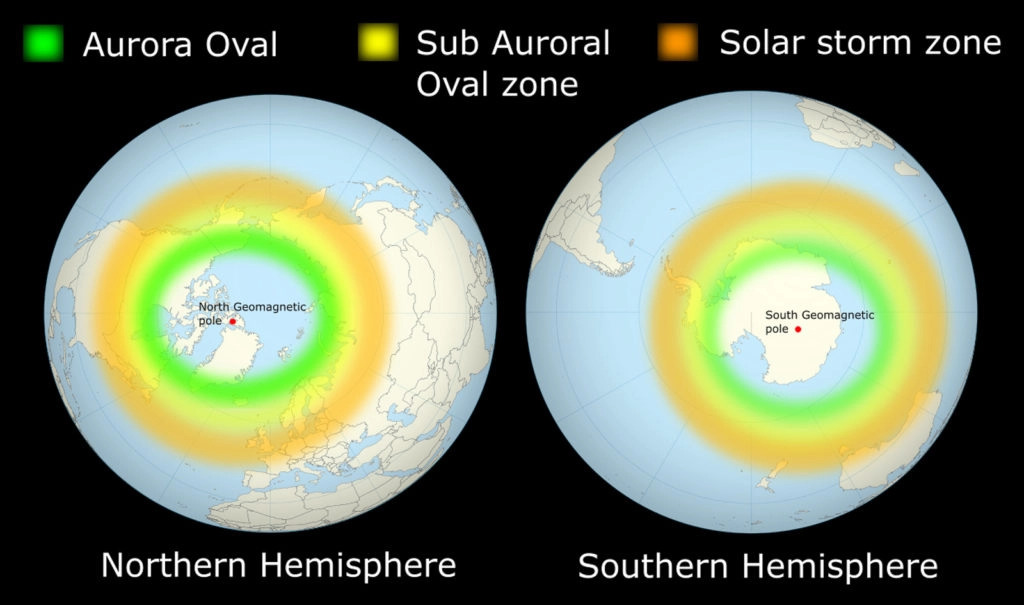

2) Location

In the northern hemisphere, the aurora is often more pronounced because you can access land mass within the aurora oval (between 60º and 75º S)

To photograph auroras in the southern hemisphere, we have a lot of ocean at this latitudes so are forced to settle with a vantage point closer to the equator than places like Norway, Iceland, & Canada provide. So unless you get to go to Antarctica, you’ll need to go beyond the aurora oval.

In addition to this, you need to find a location with little or no pollution at all.

- In the middle latitudes (above 67ºS), such as the south of Western Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand, the direction to point your camera to is paramount. Look for unobstructed views facing south.

- Closer to the pole (between 67ºS and 90ºS), in Antarctica, the aurora can happen pretty much anywhere in the sky. Contrary to the northern hemisphere, the lights often start to show up from west to east. But as the night goes on, they can occur in any direction.

Illustration by William Copeland. What are the northern lights? Sept. 2020.

URL: https://nordnorge.com/en/artikkel/what-are-the-northern-lights/.

Courtesy : Craig Crew, Aurora Australis FB page

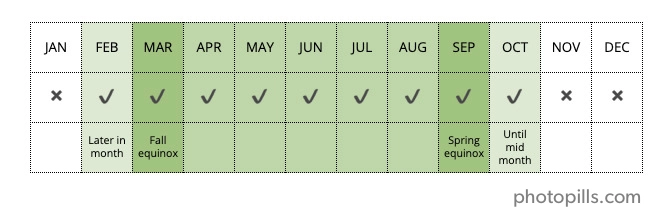

3) Time of Year

Regardless of the hemisphere you plan to travel to, spring and autumn generally provide more stable weather conditions and milder temperatures plus there is greater aurora activity around the equinoxes.

That is…

- The second and third week of March.

- The last two weeks of September.

Southern hemisphere

To see the aurora australis the best time is during the autumn and winter, from March to September. That’s when the nights are really long and super dark. During these months, the nights are really long and dark, which makes it easier to see the beautiful lights dancing in the sky. Even though these lights are always there, you can’t see them in the summer months like Nov, Dec, Jan, Feb because the sun is too bright and hides them.

4) Moon Phase

Scientifically speaking, the moon doesn’t make the northern lights stronger or weaker. In other words, you can actually photograph auroras in any moon phase.

Having said that, the moon can affect how much light there’s in the scene and, thus, how you see (and your camera captures) the aurora in the sky, the stars and the foreground:

Around New Moon or with no Moon at all (after Moonset)

When there’s a New Moon or no moon at all (you’re shooting after Moonset) it’s really dark.

In these conditions, a strong solar activity will create bright northern lights. On the other hand, a faint aurora may be difficult to see even if there is no moon visible.

When the scene is really dark your foreground will be quite dark too. So take this into account when creating your composition.

With Moon (phase less than 50%)

A bright moon may wash away the details of a faint aurora and stars, but you can still see the aurora easily.

Since the Aurora is dependent on solar activity and shifting weather patterns, a moon with a phase less than 50% has no effect on the intensity or color of the northern lights.

Depending on the Moonlight conditions, you may have enough light to capture detail in the foreground.

Around Full Moon

When the moon is full and bright, it’s like having a big flashlight in the sky, which can make the northern lights look less bright.

But seeing the big, bright moon and the northern lights together can be really cool, like a special light show. The contrast is not as great but it tends to make the sky appear a dark indigo blue.

If you’re taking pictures, the moon an help by lighting up things on the foreground, making your photos look nicer because you can include part of the landscape in your composition.

5) Terrestrial (earth / land) Weather

It’s important that the sky is clear and doesn’t have clouds covering it up!

How can you check weather

You can download the Windy application on your smartphone and tablet. You can also go to the website on your laptop and desktop computer.

Windy is available on iOS and Android.

6) Solar Weather

Usually there needs to some elevated space weather by way of CME, flare or coronal hole.

What solar activity is best for southern lights?

The brightness of the aurora is determined by the amount of solar activity in the location.

The solar activity is measured with the Kp index, the solar wind speed and intensity, and the interplanetary magnetic field strength and direction.

Even though I have posted about the limitations of Kp (being past activity and driven by Northern hemisphere magnometers), it does give us a starting point. For now, let’s use the Kp index.

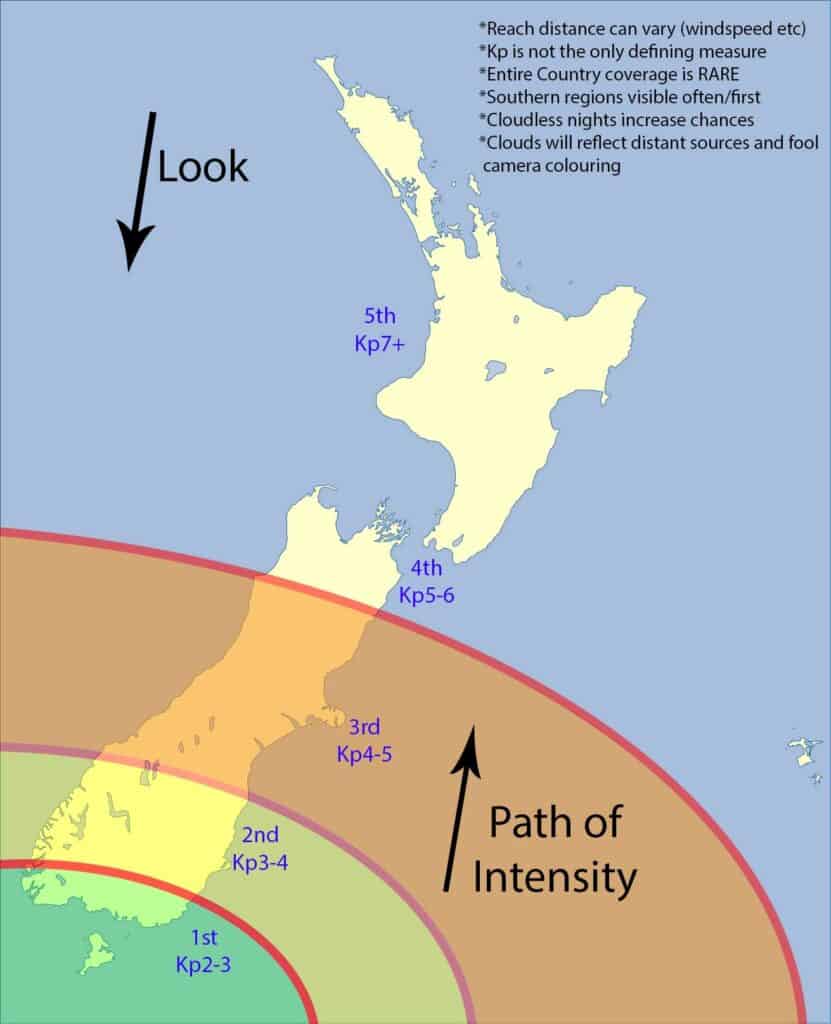

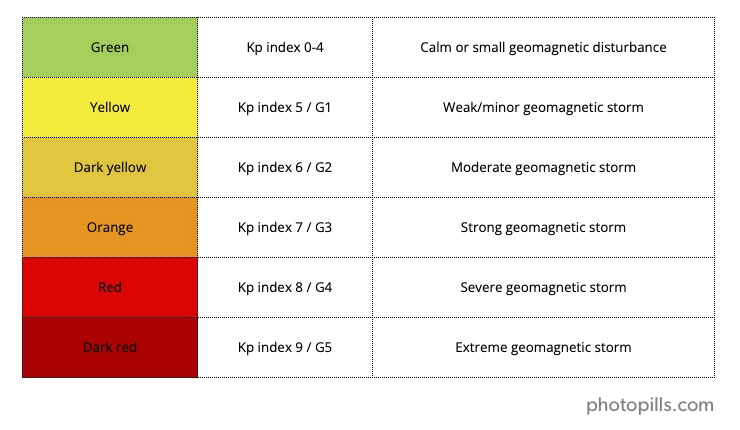

The Kp index is based on how the solar wind and Earth’s magnetic field are interacting at the moment.

It helps you guess where and how well you’ll see the northern lights. In other words, it’s like a weather forecast but for the northern / southern lights.

It measures how much the solar wind is shaking Earth’s magnetic field, on a scale from 0 to 9. A low number means not much is happening, but a high number means a big light show might be coming.

- 0 to 4: The northern lights might be quiet and faint, mostly green, and you might need a camera to really see them well.

- 5 to 6: Things get exciting! The lights move more and might show off colors like yellow, pink, or even purple. If you’re lucky, you might see a special kind of northern light called a corona, where the lights swirl directly overhead.

- 7 to 9: This is when the northern lights go all out. They can fill the sky, show rare colors like red, and be seen much further south than usual.

In places like Alaska, Canada or Iceland, a Kp 3 means a good chance of seeing the lights. But to see them in places further south, like NZ, you’d need a Kp 5 or more.

A Kp 5 or more means a solar storm of grade G1 is happening. The higher the Kp number, the stronger the storm. A Kp 9 is a very big deal and means the maximum possible storm (grade G5) is happening.

Nevertheless, the Kp-index gives you an idea of what the auroras might do, but it’s not perfect. It’s always a bit of a guess, so it’s good to check the forecast and hope for clear skies.

We will look into this some next post, with further detail just how you can gauge all this.

7) Solar Cycle

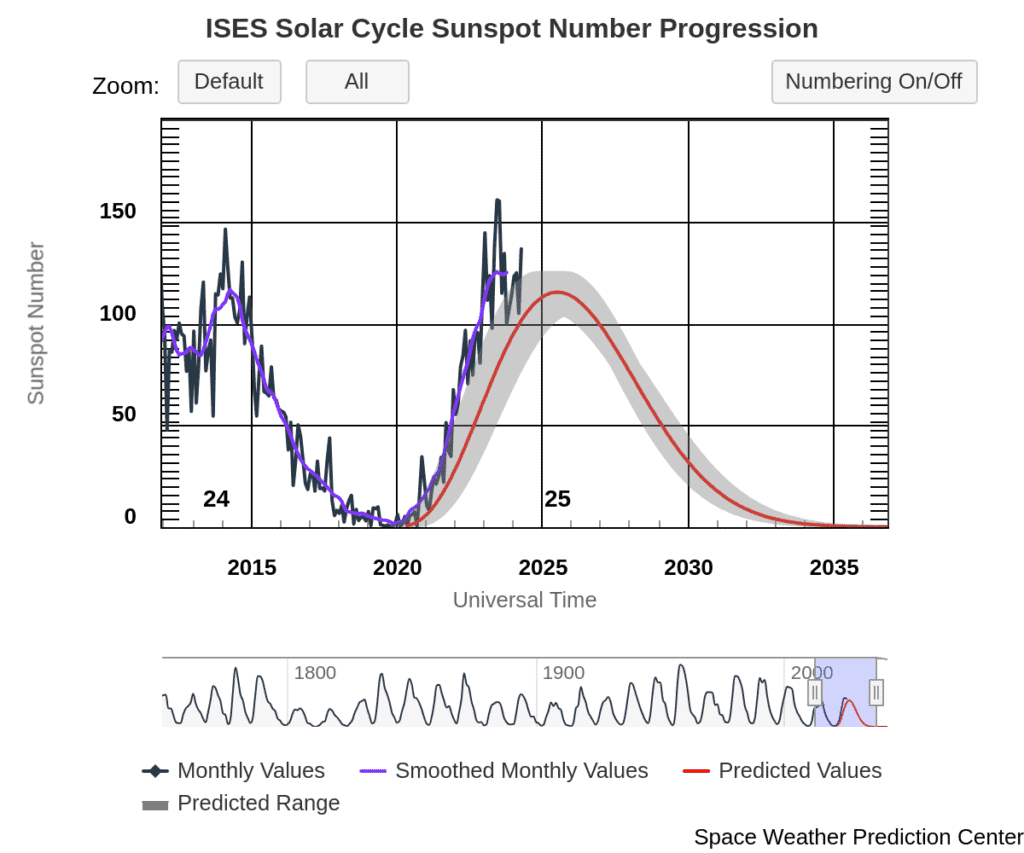

The solar cycle, also known as the solar magnetic activity cycle, sunspot cycle, or Schwabe cycle, is a nearly periodic 11-year change in the Sun‘s activity measured in terms of variations in the number of observed sunspots on the Sun’s surface. Over the period of a solar cycle, levels of solar radiation and ejection of solar material, the number and size of sunspots, solar flares, and coronal loops all exhibit a synchronized fluctuation from a period of minimum activity to a period of a maximum activity back to a period of minimum activity.

The magnetic field of the Sun flips during each solar cycle, with the flip occurring when the solar cycle is near its maximum. After two solar cycles, the Sun’s magnetic field returns to its original state, completing what is known as a Hale cycle.

This cycle has been observed for centuries by changes in the Sun’s appearance and by terrestrial phenomena such as aurora but was not clearly identified until 1843. Solar activity, driven by both the solar cycle and transient aperiodic processes, governs the environment of interplanetary space by creating space weather and impacting space- and ground-based technologies as well as the Earth’s atmosphere and also possibly climate fluctuations on scales of centuries and longer.

We are currently in cycle 25, which started Dec 2019.

Types of Auroral Observations

Credit : Ian Cooper, Astronomer, Aurora Australis NZ Facebook page.

Airglow

On the back of all this, it is probably worth a quick mention about a non Auroral phenomenon, called airglow. Whereas an aurora is driven by high-energy particles originating from the solar wind, airglow is energized by ordinary, day-to-day solar radiation. Airglow is faint luminescence of earth’s upper atmosphere that is caused by air molecules’ and atoms’ selective absorption of solar ulttraviolet and X-radiation. Unlike auroras, which are episodic and fleeting, airglow constantly shines throughout Earth’s atmosphere, and the result is a tenuous bubble of light that closely encases our entire planet. (Auroras, on the other hand, are usually constrained to Earth’s poles.) Just a tenth as bright as all the stars in the night sky, airglow is far more subdued than auroras, too dim to observe easily except in orbit or on the ground with clear, dark skies or a sensitive camera. But it’s a marker nevertheless of the dynamic region where Earth meets space.

Most of the airglow emanates from the region about 50 to 300 km (31 to 180 miles) above the surface of Earth, with the brightest area concentrated at altitudes around 97 km (60 miles). Unlike aurora, airglow does not exhibit structures such as arcs and is emitted from the entire sky at all latitudes at all times. The nocturnal phenomenon is called nightglow. Dayglow and twilight glow are related terms. Nightglow is very feeble in the visible region of the spectrum; the illumination it gives to a horizontal surface at the ground is only about the same as that from a candle at a height of 91 metres (300 feet). It is possibly about 1,000 times stronger in the infrared region.

This photochemical luminescence (which is also called chemiluminescence) is caused by the chemical reactions of incoming solar radiation with atoms and molecules present in the upper atmosphere. Sunlight supplies the energy needed to raise these materials to excited states, and they in turn produce emissions at particular wavelengths. Atmospheric scientists frequently observe emissions from Sodium (Na), hydroxyl radical (OH), molecular oxygen (O2), and atomic oxygen (O). Emissions of sodium occur in the sodium layer (some 50 to 65 km [31 to 40 miles] above Earth’s surface), whereas emissions from OH, molecular oxygen, and atomic oxygen are most concentrated at altitudes of 87 km, 95 km, and 90–100 km, respectively.

Observations from Earth’s surface and data from spacecraft and satellites indicate that much of the energy emitted during nightglow comes from recombination processes. In one such process, radiant energy is released when oxygen atoms recombine to form molecular oxygen, O2, which had originally become dissociated upon absorbing sunlight. In another process, free electrons and ions (notably ionized atomic oxygen) recombine and emit light.

In the daytime and during twilight, the process of resonance scattering of sunlight by sodium, atomic oxygen, nitrogen, and nitric oxide seems to contribute to airglow. Moreover, interactions between cosmic rays from deep space and neutral atoms and molecules of the upper atmosphere may play a role in both the nocturnal and daytime phenomena in the high latitudes.

So sometimes when out taking photos, it looks like you might have an aurora, despite no space weather indicating an auroral event. When that is the case, it is most probable you have captured airglow instead.

Credit : https://www.britannica.com/science/airglow

Additional credit : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_cycle